Use it wisely.

Time is one of the most precious commodities we have. In each day we get 24 hours and how we spend much of it is determined by need. We sleep, we eat, we work. Therefore, when the opportunity comes around for educators to spend time together, as a department, it is critical that we use this time wisely.

I have written before about using Teams and Emails effectively to reduce the burden of administrative tasks. For me, such tasks have no place in a curriculum team meeting. This precious time should be used to:

- Develop teachers.

- Develop curriculum.

In my school we have directed departmental time called “CPDS” (Curriculum Planning Developmental Sessions). It is in these sessions my team and I work on the application of the curriculum (I refuse to say “implementation”!) both in terms of teacher actions and resourcing. Determining how to use these sessions is something I consider very carefully, and I base it on data.

How do you know?

I am incredibly careful about what can be inferred from processes such as “book-looks.” Sometimes they mask what the pupil knows and does not yet know. However, with a little care and experience, these actions can yield interesting lines of inquiry for departmental improvement. Furthermore, if you as a leader spend time looking at book’s and popping into lessons then do not act, what was the point?! You could argue a step further and say you are not serving your team by providing feedback and development that will move your staff and your pupils on.

Example 1 – Explanations.

A good explanation is worth its weight in gold. We provide our team with resources so that they may use some of their planning time thinking about and refining their explanations. Sounds good right?

Last term during my usual stroll around the department, I noticed staff still resisting to use the visualizer for certain types of explanations. This suggested one or more of the following:

- Use of the visualizer is not yet habitual.

- Staff may not yet be as confident with explanations.

- Staff may be stuck in old habits.

- They had a bad morning and have not got themselves set (it happens)

So, I decided to use our next CPDS session to target this in a supportive way. Beforehand we happened to have a shortened academic meeting of 30 minutes (usually used for checking in on day-to-day issues). Within that time my Lead Practitioner provided an example of a high-quality explanation over the visualizer. This involved him labelling the heart and questioning the “students” (the staff) via mini whiteboards. Once the explanation was completed the department engaged in an open-ended discussion about how this may benefit their upcoming lessons. It was at this stage I dropped the following bombshell:

“Next week in our CPDS session, each of you will provide a similar explanation via the visualizer to the rest of the team. You may choose your own topic which must be sent over to me via teams in the next couple of days.”

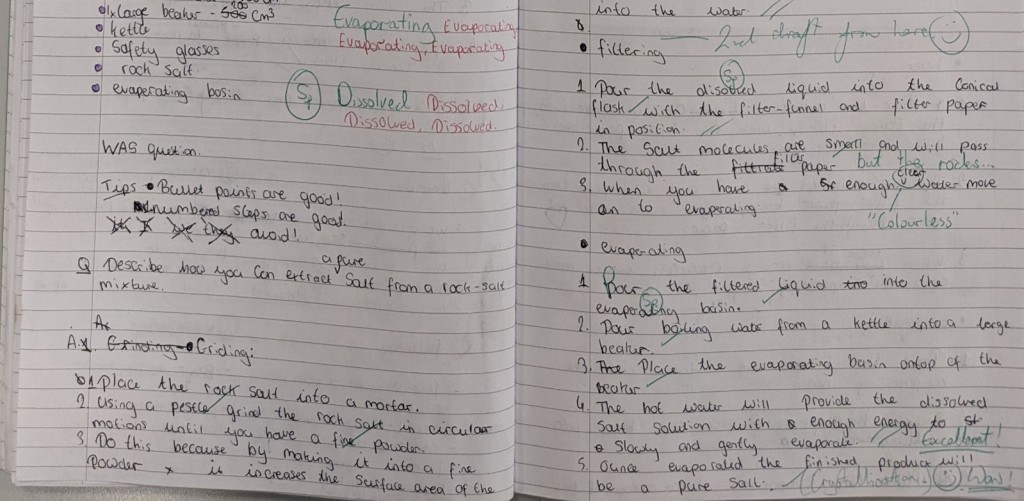

The following week I set up a random running order and my team set to it! (Me included of course, I do not ask of my team what I am not prepared to do myself.) We spent between 5-10 minutes in the next CPDS session each pretending to be a teacher in the classroom whilst others participated as students. After each explanation, we engaged in a short bit of feedback. Benefits of this session included:

- The staff witnessed seven examples from across the curriculum, including electrolysis, latent heat, resistance in a wire, and food webs – great subject knowledge enhancement!

- All staff provided feedback and so were thinking critically about the process of explanation.

- Staff left with innovative ideas for teaching. Indeed, I have been teaching for 16 years and had not considered explaining Latent Heat the way my colleague of just two years did! I used her explanation in my lesson the very next day and was buzzing about it!

- Staff realised they are not alone! We have a range of experiences, but we work together in our development of the department.

- Visualizers are now being used more frequently when I tour my department!

This is still a work in progress however this was one of the most powerful hours of curriculum development we have done to date.

Example 2 – Key Questions.

Something else that had been bothering me was the consistency of language being used in KS3. We have done an incredible amount of work over the past few years developing our resources, and schemes of learning however We did not yet have an agreed set of centralised standards for the answers to certain questions, such as:

- What is an atom?

- What is friction?

Its not that staff were giving the pupils incorrect information, but we did not have the uniformity which would ultimately strengthen the curriculum and the confidence of our pupils.

So, in the next CPDS session I opened with a mini-whiteboard task. I asked my team the following (notice the front loading…):

“By writing an answer on your whiteboard, without conferring, define what an atom is.”

Every member of my team gave me differing responses, but all “correct.” Two such examples were:

“The smallest part of a substance”

“Made from protons, electrons, and neutrons.”

You could see several jaws hit the floor in that moment. The point had been well made and the buy-in was well and truly secured for the next steps. To an 11 year old year 7 moving through year groups, encountering different science teachers, confusion could emerge.

So, what did we do?

We agreed to write a set of “Key Questions” in our subject specialist teams (this is totally core questions btw). We used a KS3 Retrieval Roulette as a starting point and edited the sheet to suit our curriculum sequence and topic names. This took place over the next couple of CPDS sessions and Y11/Y13 gained time. The result? 658 questions and answers that we now use for:

- Cover work

- Review lessons

- Home learning (sent home on the back of their knowledge organisers)

Most importantly we now teach with more consistency. We encourage pupils to express their responses as individuals however we have an agreed core set of responses we teach in the first instance. (WTTEO is very much rewarded!) Our next step, following a highly successful introduction, is to develop these for KS4 this term.

Do not waste what time you have.

Whether you are a Head of Science or a leader in another area, time is a resource we cannot reuse, cannot produce, and therefore we must not waste. On the backdrop of what is becoming and increasingly challenging profession we have a duty of care to our staff and to our pupils to ensure that the time we get to meet, is used as effectively as possible.

Hopefully, this post has provided food for thought! Feel free to drop me a comment below or catch up with me over on social media.

Thanks for dropping by.

Threads – @djgteaching

X – @djgteaching